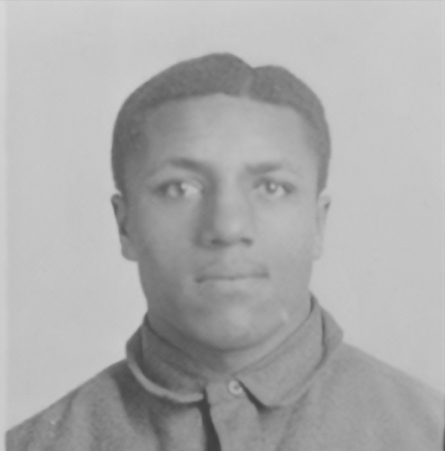

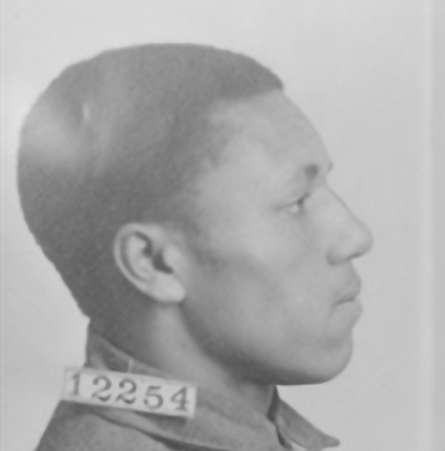

Pvt. Abner Davis

Abner Davis was born in Kentucky on June 29, 1893, Kentucky. He quit school at age 15 in the sixth grade and worked with his father as a janitor until he enlisted in the army in September 1914. He had two SCMs on his military record (see below) and no record of civil offenses.

His prison evaluation record states, “This man has a slightly bad record in the U.S. Penitentiary.” It went on to say, “The prisoner was, at the time of the trial, 24 years of age, and had been in the Service about two years and two months. Records of two previous convictions were introduced, for disrespect to a non-commissioned officer, being drunk in uniform, and engaging in a fight in ranks while on a practice march.” He was convicted on all charges: “willful disobedience of an order of his superior officer, in violation of the 64th Article of War; of murder, in violation of the 92nd Article of War; and of assault to commit murder, in violation of the 93rd Article of War. Sentenced to life imprisonment at hard labor.”

From the U.S. v Tillman trial transcript: “It cannot be reasonably doubted, that some of the men of the 3rd Battalion were impelled by fear to flee the camp-site when the firing first broke out and to seek refuge in various places beyond its confines. Nor is it improbable that some were apprehensive and filled with fear lest their comrades, who had gone forth with the column, would return and carry out their threats to ‘shoot up the camp’ and all those who refused to join the mutineers in their descent upon the city. Therefore, mere absence from the checks which were taken, or from the camp-site, or from any given proper station fails to establish the element of willful disobedience of orders, of mutiny, of murder, or of assault to commit murder.” This has a direct bearing on the question of Davis’ guilt or innocence because he was convicted largely on the basis of claim that he was not accounted for in the checks in camp that night.

When the clemency board reviewed Davis’s case in March 25, 1919, it concluded, “The evidence for the prosecution is sufficient to show that Davis disobeyed the order to remain in camp, and his own statement that he took part in the rush on the supply tent and got a rifle and ammunition, is sufficient to convict him of mutiny. The doubt which arises is whether the evidence is sufficient to sustain the finding of guilty of murder and assault with intent to commit murder.”

This was vehemently countered by a memo to the Secretary of War from the JAG, dated July 16, 1919, signed by Colonel Edward Kreger, the Acting JAG. Kreger wrote:

There is no evidence that Davis was in the column which marched on the city of Houston, or that he participated in any of the discussions about going to town, or in fact that he had any knowledge of the intention of any of the other men to go to town. The only evidence is his admission that he took part in the rush on the supply tent, and that he was seen returning to camp [from the direction of Camp Logan] next morning with his rifle. The mere fact that he returned to camp with his rifle is not of itself sufficient to convict him of mutiny or participating in the riot in the City of Houston. The only theory upon which he can be connected upon the charges of murder and assault with intent to commit murder is that he, having joined in the conspiracy to commit an unlawful act, became a co-conspirator and liable for the acts of the others.

“From the fact that Davis participated in the rush on the supply tent, it does not necessarily follow that he did so with intention to march upon the city of Houston. When the cry was raised that a mob was coming, practically all the members of his company rushed and got their rifles and ammunition. It is not contended that they all had the intention of going to Houston at this time, and in fact less than one-fourth of the members of the company left the camp according to the check which was made. The mere fact that he got his rifle then is not enough to show that he did so with the intention of committing any unlawful acts. It is just as reasonable to say that his intention was to protect the camp and himself from a mob, as did three-fourths of the men in the other company. There must be some evidence of an intention. The finding therefore that the act was with the intention to march upon the city of Houston to the injury of persons or property located therein, is not sustained by the evidence.

“Any soldier who participated in the mutiny with the intention of marching upon the city and committing unlawful acts was responsible for all the acts committed by those who actually did visit the city, even though he himself did not leave the camp. If he did not have such intention, then he is not responsible for the acts of the others. Having failed to produce any evidence to show such intention on the part of Davis, it was then [incumbent] on the prosecution to show that he did actually participate in the murders and assault. This it failed to do, and there is therefore no evidence to support the findings…

“The prosecution must show beyond a reasonable doubt that the accused was present in the column, and while the court might consider the fact that his statement was shown to be false, it could not use his statement that he was at one place as affirmative evidence that he was at another particular place. No matter how improbable his story as to where he actually was might appear, the court may not say that because he was not there, therefore he was in the column, where he was charged with being. This would be using the charge as evidence and throwing the burden on the accused to show affirmatively that he was not where he was charged with being, which can never be done. In view of the fact that the evidence does not sustain the findings of guilty of murder and assault to commit murder, it is recommended that the unexecuted portion of the sentence in this case, in excess of confinement for seven years, be remitted.

It also became clear that Davis was the victim of a case of mistaken identity. In a memo from the JAG to the Secretary of War, dated July 16, 1919, the JAG stated, “Captain Sorensen testified that Ira Davis and Ben Cecil, both of Company I, were turned over to him by Privates Breeseman and Sheehan, and that he delivered the prisoners to the sheriff or deputy sheriff and took a receipt for them. It thus appears that the reviewer, when he approved the findings, was under the erroneous impression that Abner Davis had been arrested in the city of Houston on the day after the riot.” [underlines in the original]

A handwritten internal memo in the JAG Office, addressed to Col. Ely, dated December 9, 1919, says, “Because of the meagre evidence it is believed that he might be punished about the same as the men convicted of mutiny only, but if recommendation for reduction is made now it will precipitate an avalanche of applications from the others. It is believed that when he has been sufficiently punished the sentence may then be remitted, or at least, at some later date.” The memo is signed, “Col. Read,” co-signed by Colonel King with the notation “I concur.”

In December 1920 the JAG replied to an inquiry on Davis’ case from Congressman King Swope, using the standard format. Swope had written to the JAG asking for a copy of the court-martial record “with a view of making application for pardon” after receiving a letter from Davis requesting the congressman’s intervention on his behalf.

When the clemency board reviewed Davis’ case in April 1924, it noted that he was working as the chaplain’s orderly in the prison, and that his record of conduct had been clear since April 1922. The board concluded, “In view of all the circumstances, it is recommended that so much of the sentence to confinement in this case as exceeds twenty-three years and three months be remitted.”

In 1931 Davis was still incarcerated on his reduced sentence of 23-plus years. On August 3 of that year the JAG wrote to the AG’s office in response to a request for “remark and recommendation… relative to clemency in behalf of Abner Davis.” The JAG referred to the original review of the case, which was conducted in 1919, and concluded, “As Davis was convicted of participating in the murder of fourteen people and assault with intent to commit kill eight other persons, this office does not feel warranted in recommending any further extension of

clemency than has heretofore been granted.”

Davis died in 1966.