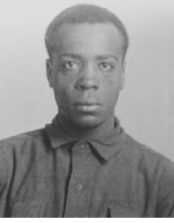

Pvt. James R. Hawkins

James Hawkins was born in Virginia in 1895 and enlisted into the army in April 1912. His prison record during his incarceration at Leavenworth says, “Quit school at the age of thirteen years in the second grade… He was well behaved and honest, faithful and very industrious… he was never in any trouble of any kind… All correspondents speak well of him…Company Commander states that this man was a very good soldier and considered an asset to the Company.” It concluded, “Has a good record in the U.S. Penitentiary.” If the record is correct that Hawkins only completed the second grade in school, then he was certainly an intelligent man who must have continued his informal education while he was in the army, because his letters from prison show him to be a very articulate writer.

While incarcerated at Leavenworth, Hawkins was the signatory of a typewritten letter dated May 14, 1919, sent to Lt. Col. Samuel T. Ansell (Acting JAG) which read:

I am appealing to you, not for myself alone, but for me and my imprisoned comrades now confined for participating in the Houston Riot, on August 23rd 1917… We come not as a body making a demand, but we make an appeal. We ask you to consider the fact that we were in the south, in the State of Texas, where the negro is unanimously hated whether in uniform or not. We do not think this [the riot] could have occurred in any other state in the union. Every time negro soldiers have been put in this state (Texas) they have had trouble. We know that public opinion demanded that we be punished, but this opinion was most erroneously formed. It is believed by some that it was an error on the part of the War Department, to send negro soldiers into Texas. This I have no authority to criticize, but I will say that we had no authority as soldiers on guard. We were not allowed to load our rifles at night, though it may be one of impenetrable [sic] darkness. We ask you to consider the record of this regiment prior to this trouble. It was not excellent – it was magnificent. We were in a city and state where each time we went on the street we were greeted with the vulgar word ‘nigger.’ What is a nigger? Can a nigger wear a uniform? We ask you to consider that this trouble was started by the police of Houston, and not by the 24th Infantry. These soldiers were often beaten up, but not wanting to start any trouble they passed it up. This was almost passed up until the camp was attacked, but what soldier would not feel resentful upon seeing his comrades come to camp beaten up by a policeman, just because he is a negro. It is all we can do to ask you to consider our case from these facts. I ask you to consider the testimony that I am sending you. I say the camp was attacked, the evidence framed up, and that we were unfairly tried. If this does not confirm my statement, then my labor has been in vain… every man in this body would rather be lying beneath the sod in the ‘Argonne Forest’ than be a prisoner for this alleged crime… To be kept out of the war has punished us. We would rather of had a headboard mark out resting place in a soldiers grave, marked ‘killed in action,’ than have a court determine our living grave. We ask you to consider our case to the best of your ability, give us a chance to be in the future what we have been in the past; honorable soldiers.” Signed James R. Hawkins, Late Private Co. I, 24th Infantry.

That letter was amended to a memorandum from the Military Justice Division of the AG’s office, which stated, “The Examining Board sees no reason why he should not make a good soldier, but does not recommend his transfer to the Disciplinary Barracks by reason of his crime. Clemency is not recommended.”

Hawkins was released from the penitentiary and transferred to the USDB on June 9, 1927, along with John Adams, Fred Brown, Walter Burkett, Allie C. Butler, Walter T. Johnson, Leroy Pinkett, Harry Richardson, Luther Ricker, Jessie Sullivan, and Joseph Wardlow. At that date, their sentences were set to run to February 9, 1937.

In 1934, after he was finally released from prison, Hawkins wrote an article that was published in The Chicago Defender (National edition) (1921-1967); Mar 17, 1934, that offered the first extensive, first-person account of the trouble in Houston and its antecedents ever written by any former member of 3/24 Infantry.